🎨 Color-coded CRIBS

What if you could look at your draft and instantly understand how a reader felt about it? Imagine being able to scan your document and get a real-time sense of how each sentence is performing. What if you could see where the pain points and dopamine hits were hidden?

Here's a 2,000 word draft of an essay I'm working out. Since my editor and I share a common visual language, I know what these colors mean. I can see the whole essay at once, and quickly know where I need to dive in to fix it.

For several years I've been obsessed with the idea of bringing "visual" languages to non-visual mediums. In architecture school, I learned a language for diagramming buildings. How can it be translated for writers?

You can think of "color-coded CRIBS" as the light-weight and peer-to-peer version of the kind of visual feedback I give in the Writing Studio. It's fun, anyone can learn it, and students were blown away by how valuable it was.

Boom, you're on your way to evolving into one of those octopus-aliens from Arrival. (Spoiler ahead)

In this movie, based off a Ted Schiang novel, the "Heptapods" arrive in a 300' tall egg-looking ship. They come in peace. We're lured into their ship, and they introduce themselves by squirting these ink-looking rings in front of them. This is their language? The humans spend all movie deciphering how to read these things. They finally get it: Each ring represents a complete thought - A paragraph, a full idea, maybe even an entire tweet-thread.

Humans have a high-friction way to communicate meaning. We read a string of glyphs, convert them into words, and then convert words into meaning. But the Heptapods comprehend meaning through a sophisticated visual language. We're not fully there yet. Maybe emoji's are an evolutionary turning point. (Proof: Moby Dick has already been converted into "Emoji Dick," the Herman Melville classic, but strictly through emojis.)

Our goal here in Write of Passage is to build a simple and shared language. If we can all interpret the same five colors in the same way, then we'll all gain a superpower: The ability to quickly and accurately know how our essay resonates with a reader.

CRIBS

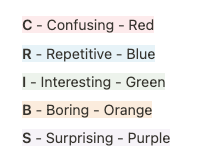

CRIBS is a popular feedback system within Write of Passage. We might as well use it as the basis for our colors. For anyone new to this system, you can check out David Perell's essay on CRIBS. It's a simple acronym. The first time you implement this, you might need to refer back to this legend. But, it's easy to memorize, and it's intuitive after you do it once or twice.

Highlighting

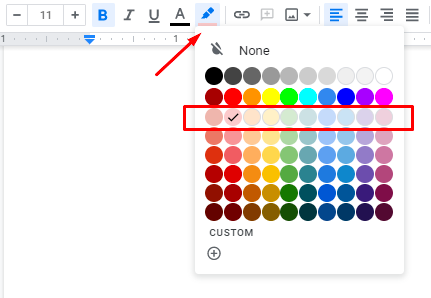

You can access the highlight menu from the top bar in Google Docs. The third row is the clearest to read. I recommend not using yellow since it's the default color for comments. Remember: You don't have to highlight every sentence!

Confusing - light red 3

- I had to read this twice, and still don’t fully understand it

- Too many ideas in one sentence

- Complex phrasing (academic instead of "bar talk")

- The sentence is too general, and I'm not sure what you mean

- Too abstract

- No specific examples, images, symbols

Repeated - light blue 3

- This idea is already covered in a different sentence.

- You don’t lose anything by removing this.

Interesting - light green 3

- I learned something, about the idea or the author

- I was able to understand what you meant

- I was able to see the scene you were painting

- There is a natural flow from idea to idea

Boring - light orange 3

- There’s a lot of information in this sentence that doesn’t trigger a response

- I caught myself thinking about something else as I was reading this

- The information here doesn’t seem relevant

Surprising - light purple 3

- I’m curious to learn more about this

- I didn’t know or expect this

Commenting

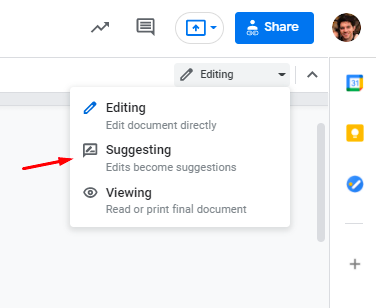

If you highlight sentences in "Suggesting" mode, then a comment will pop up for every highlight you make. This gives you the ability to explain WHY you gave a sentence the color you did. This can be helpful for the author. It helps them know why you assigned the color you did.

Here's an idea for the type of comment you can leave for each color:

Confusing: ask a clarifying question– A specific question from a confused reader can show the author what's missing in a sentence.

Repetitive: point to where else the idea occurs– This helps the author decide which of the two ideas can be cut

Interesting: share your impression– Added context on why something is interesting can help the author add color around it

Boring: confess why you tuned out– Confessing specifically where and why you were ready to dip can show the author retain readers

Surprising: ask a question to learn more– By sharing specifically what you're curious about, it shows the author where to potentially go next

Implementing

Okay, so your document is filled with color. Now what?

Here are three things to keep in mind when implementing.

Pain Points

Your first step is to address anything that is confusing, repetitive, or boring. This is where your friction lies. This is where readers will flee. Make an effort to edit or completely re-write these sentences. You might want to even consider re-writing the paragraph that this sentence occurs in, since you can't be sure exactly where the root issue is.

Compression

If you see any long stretches without color (300+ words), it could be a cue for compression. Sure, maybe it wasn't a pain point, but if it isn't interesting or surprising, then maybe it can be shorter? Challenge yourself to reduce these long stretches to half of their length. You want to deliver the reader to the next dopamine hit (interest or surprise) as soon as you can.

Polishing

Take a look at the sentences that are interesting and surprising. Did the reader leave a comment around why the felt the way they did? Maybe you can add some additional context to further expand on what caught the reader's attention. You can also be strategic around placing these shots of interest. Is it worth moving a purple chunk up to the introduction so that the reader is hooked?

Sharing Your Document

In case you haven't shared a Google Document for feedback, here are the steps you need to take before you post a link to your draft.

1.

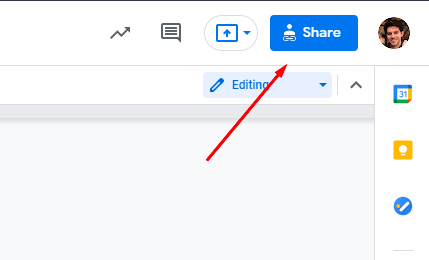

Click the blue “Share” button on the top right.

2.

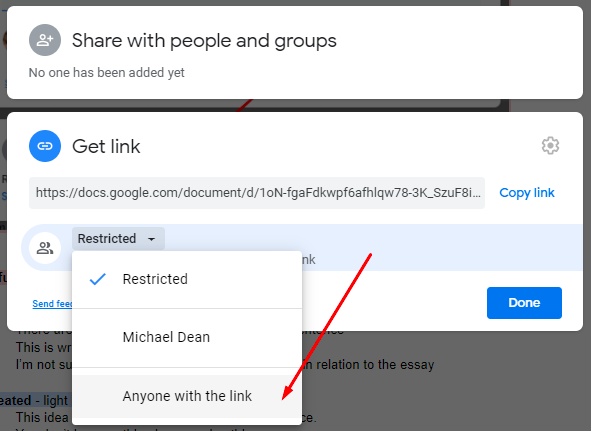

Click the "Get link" box.

3.

First click "Restricted" top open the dropdown menu, and then click "Anyone with the link."

4.

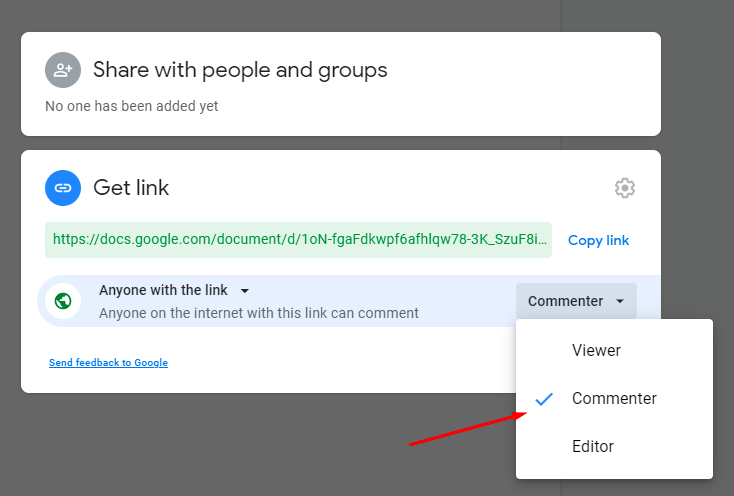

First click "Viewer" on the right to open the dropdown menu, then click "Commenter."

Dean's List

Join to get new posts in your inbox.