🥩 Hunter's Breakfast Myth

Last weekend my wife and I found ourselves staying at a bed and breakfast on Greenwood Lake. When she told me she loved breakfast, I told her "no, THIS guy loves breakfast." I pulled up the radical Hunter S. Thompson quote and read it to her as we waited for some eggs and bacon.

“Breakfast is the only meal of the day that I tend to view with the same kind of traditionalized reverence that most people associate with Lunch and Dinner. I like to eat breakfast alone, and almost never before noon; anybody with a terminally jangled lifestyle needs at least one psychic anchor every twenty-four hours, and mine is breakfast. In Hong Kong, Dallas or at home — and regardless of whether or not I have been to bed — breakfast is a personal ritual that can only be properly observed alone, and in a spirit of genuine excess. The food factor should always be massive: four Bloody Marys, two grapefruits, a pot of coffee, Rangoon crepes, a half-pound of either sausage, bacon, or corned beef hash with diced chiles, a Spanish omelette or eggs Benedict, a quart of milk, a chopped lemon for random seasoning, and something like a slice of Key lime pie, two margaritas, and six lines of the best cocaine for dessert… Right, and there should also be two or three newspapers, all mail and messages, a telephone, a notebook for planning the next twenty-four hours and at least one source of good music… All of which should be dealt with outside, in the warmth of a hot sun, and preferably stone naked.”

As I read it, she was hooked, with intermittent gasps, eye-widens, and crack-ups. Our table was soon filled with plates, and it felt wimpy compared to the legend we just heard. This breakfast ritual is absurd enough to grab anyone's attention. But behind the hyperbole is an unconscious mastery of craft. It's the difference between a crazy idea and a classic.

This was written in 1979, six years after Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and two decades after that time where he notoriously rewrote Hemmingway novels (while speaking them out loud). I imagine this 215 word piece was blurted out in around 25 minutes, perhaps under the influence of eggs and cocaine, and in a rush to meet a deadline for Lapham's Quarterly.

Even if the act of making this happened in a flash, there's a lot we can learn from carefully analyzing Hunter's writing mechanics. We're about to dive deep into an analysis that is six times longer than the piece itself. The goal here is to identify the rational patterns behind emotional resonance.

Here are some takeaways from the piece that I look to carry through into my own work:

- If our essay contains a series of ideas, we should consider not just how we arrange them, but how far we unpack each one.

- I know what it feels like when a sentence starts normally, but then hits you in the face with a punchline from left field.

- We can write sentences at near infinite length if we consider how each phrase builds momentum into the next one.

- Capitalizing words that typically don't get upper-cased can bring flat words to life, especially if you add context clues.

- When you repeat a distinct phrase at the beginning and end of an essay, it implies resolution, and also gives the opportunity for a surprise ending.

1. The relative weight of meaning

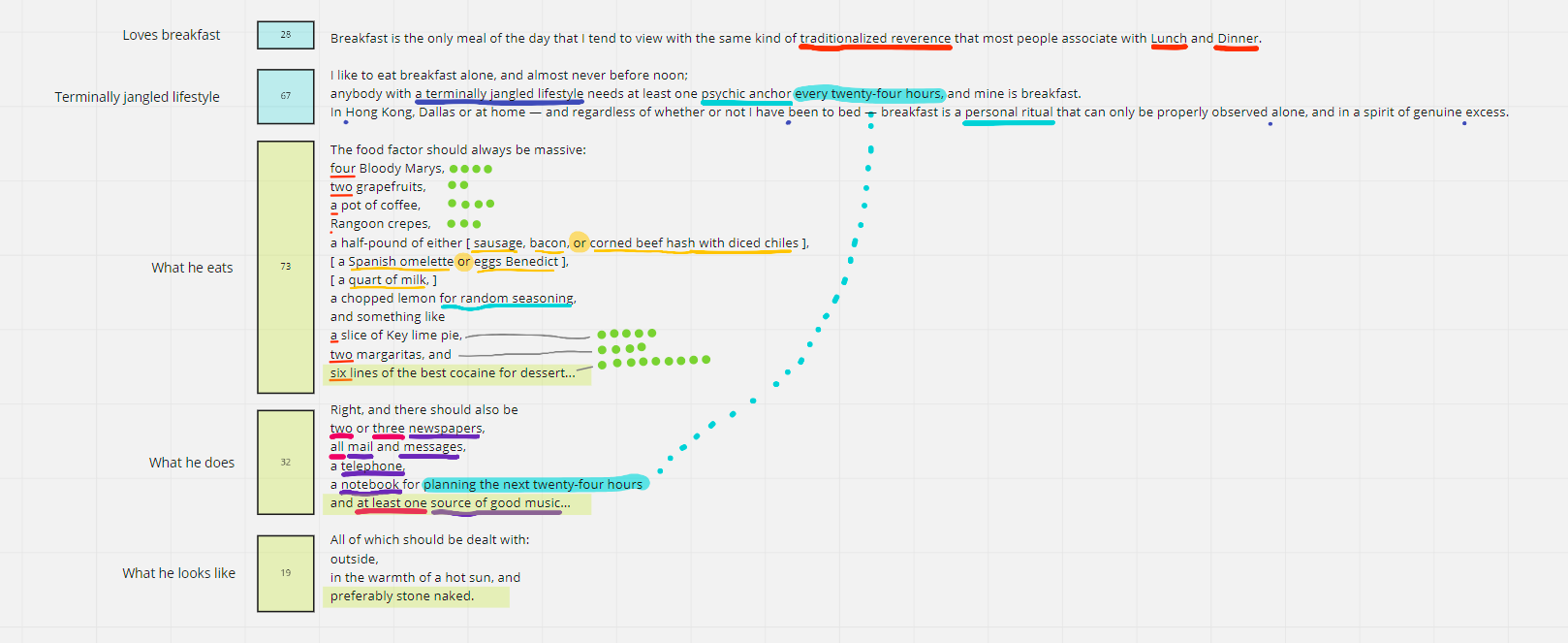

Even though this quote often comes in as a formatless chunk of text, there are 5 core "sections." Each one covers a distinct dimension of meaning.

- This guy loves breakfast —- 1 ****sentence, 28 words

2. This guy lives a "terminally jangled" lifestyle —- 3 sentences, 67 words

3. This is what he eats (whoa) —- 1 sentence, 73 words

4. This is what he does while he eats —- 1 sentence, 32 words

5. This is what he looks like while he eats (naked in nature) —- 1 sentence, 19 words

If we visualize the relative length of each section, we can see that each of these ideas are NOT covered equally. An X represents 10 words.

1 - XX

2 - XXXXXX

3 - XXXXXXX

4 - XXX

5 - X

Not only is each section a different length, but there is natural "crescendo." There is a progression in how far he unpacks an idea: A quick jab, some detail, a single-sentence marathon, a wind-down, then a final jab.

The middle chunk, which is an immersive 73 word sentence, listing 14 items, is the core of the piece. If the other 5 sections were covered at equal length, this killer sentence wouldn't stand out as much. By weighting and arranging meaning, your structure can create a "spotlight" that brings attention to the most critical idea.

Part of the skill in writing a balanced composition is knowing when and where to get into detail. Any one of these 5 sections could be expanded to be 10x the length. But it's not about length, it's about balance. He could've wrote a trippy 100 word outro section describing what it's like to eat oudoors, but all he had to say was "in the warmth of a hot sun, and preferably stone naked," and he nailed it.

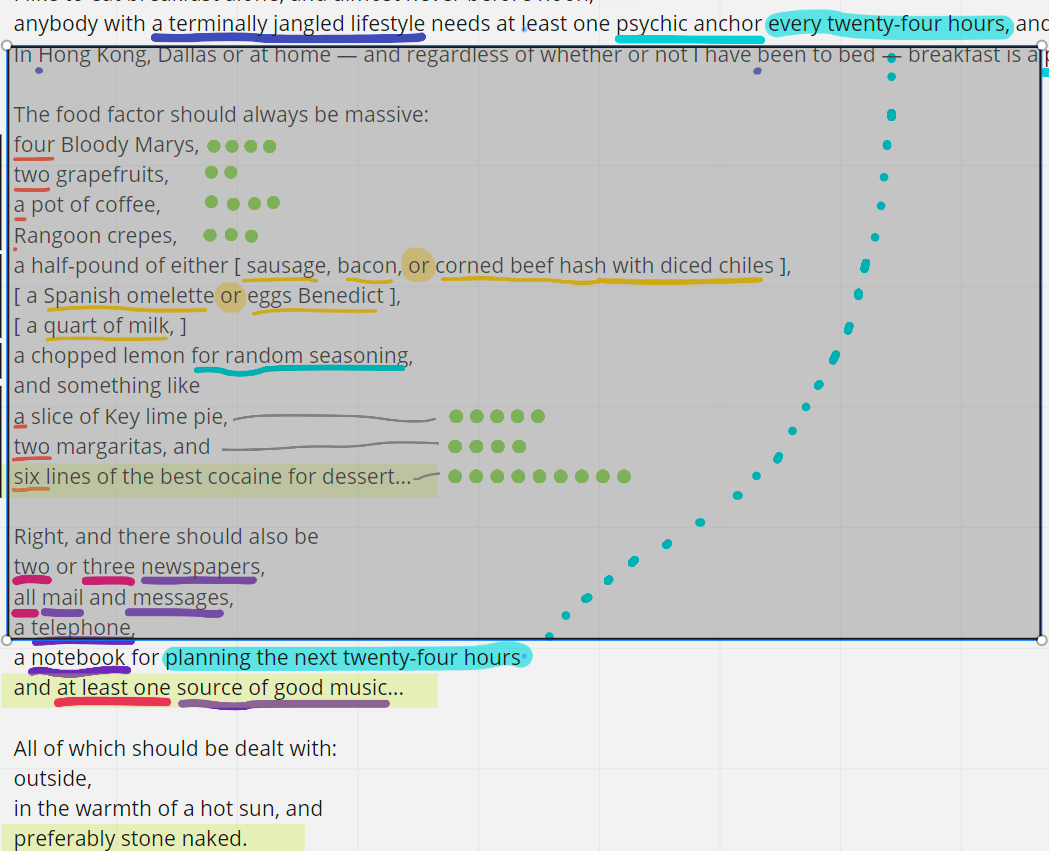

2. End with the shock

While sections 1 and 2 are about "telling" the reader, sections 3, 4, and 5 are about "showing" the reader. The author paints a visual scene, where we can see what he eats, what he does while he's eating, and what he looks like.

While each sentence is loaded with images (23 total), the last image of each sentence is a shocker that lodges the whole section into your memory. It's a punchline. It's not only funny, but it ties back to and enforces the "terminally jangled lifestyle" idea from the beginning of the piece.

What does he eat?

- The sentence: an excessive list of 13 breakfast items

- The shocker: he finishes breakfast with six lines of cocaine

What does he do while he eats?

- The sentence: he answers letter and returns calls

- The shocker: there's a jungle of noise while he does things that typically require focus ("at least one" good source of music)

Where does he eat?

- The sentence: out in nature, in the hot sun

- The shocker: he's naked

Each paragraph starts modestly, sometimes dovetails into excess, but consistently lands at something out of the ordinary.

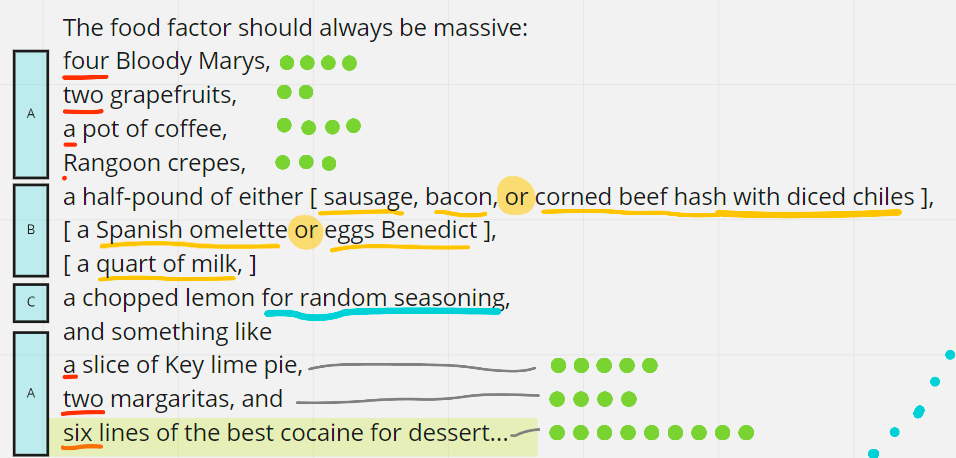

3. The run-on sentence

33% of this essay is a single sentence where Hunter describes the 14 staples of his breakfast menu. This is a textbook run-on sentence, but Hunter uses some clever devices to make each item roll into the next.

A - Number cascades

Notice how in the beginning, the number of items reduces: 4, 2, 1, 0. Then in the end, the number of items increases: 1, 2, 6. Not only do the cascading numbers create momentum, but they add context, scale, and curiosity to the items that follow them.

4 Bloody Mary's ... he's looking to get wasted?

2 Grapfruits ... why two?

A pot of coffee ... by himself?

Check out how the rhythm and meaning of each object changes from phrase to phrase.

Blood-y-Mar-y

- 4 syllables | 2 words

- a drink that gets you wasted

Grape-fruit

- 2 syllable | 1 word

- something healthy

Pot-of-cof-fee

- 4 syllables | 3 words

- something that caffeinates a group of 3

Ran-goon-crepes

- 3 syllables | 2 words

- a type of crepe, what is a Rangoon?

This kind of variation makes it engaging to move from phrase to phrase. Think of how boring a list would be that was: an orange, a kiwi, a sausage, a waffle. This list has identical quantities. It's filled with 2-syllable solid foods that don't imply any kind of situation.

By iterating on quantity, phrase structure, and meaning from line to line, there is constant forward momentum. A sentence can be as long as you want it to be, and even the comma police might let it slide.

B - Shrinking sets

After his item count goes from 4 to 0, he switches from numbers to weight: a half-pound. From this point on, instead of describing single things, he's describing a set of possible things. Every day, he has either a half-pound of either sausage, bacon, OR corned beef hash.

The next sentence also has an OR, indicating another option between a Spanish omlette and an Eggs Benedict. Notice how the size of the set reduced from 3 to 2.

The next sentence doesn't haven an OR. This implies a set of 1. Without using numbers, he used a set of things to imply scale, and he reduced that scale each line. This final line is a singular image of him chugging an entire quart of milk.

C - Screwball

After the shrinking set, he throws in a, "chopped lemon FOR random seasoning." This is the first time he describes WHY something is part of his routine. It paints the image of an uncivilized beast, wielding a lemon in his left hand, squeezing juice on whatever he comes across.

Where parts A and B were sequences with momentum, this image is a one-off pivot. It prepares us for the punchline. It's a quick lapse in the sequences he engrained in us before. It's like a wind break before the final sequence: the 1 > 2 > 6 > "cocaine!" punchline.

4. Breaking the rules of capitalization

The first sentence uses the word "reverence" and then capitalizes Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner in the way that God gets capitalized. Meals of the day aren't typically upper-case. By making that decision, in close context to a holy word (reverence), we get the sense that breakfast is Hunter's religion.

We have certain standards for capitalization:

- The first word of a sentence

- Names of people or places or things

- Months and Days

- The self ("I")

Choosing to break these rules, paired with nearby context clues, can add a new dimension to flat words.

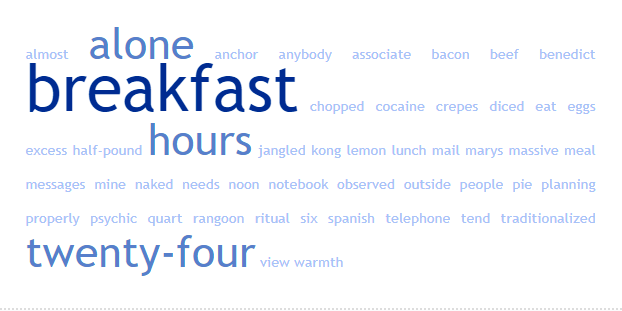

5. Book-end repetition

Only three phrases appear in this essay more than once:

- Breakfast

- Alone

- Twenty-four hours

Breakfast and alone appear 2-3 times in the first two sections. When repetition is done up front, within close proximity to each other, it helps enforce and frame what is coming next. It's super clear that this essay will be about breakfast. We expect him to describe a ritual that is private.

But the repetition of twenty-four hours is different because it exists at both the beginning AND the end of the piece. The first time you see it, it draws your attention. Instead of saying a day, spelling it out in hours gives us the sense that Hunter might be working in 24 hour sprints. When we common across it again near the end, the reader has new context on how "terminally jangled" the author really is. It ties us back to the intro, and the idea of breakfast as a "psychic anchor."

This phrase acts as a book-end that opens and closes the meat of the essay. It brings a sense of resolution. But it's like a fake-out ending, because it's followed up by the image of Hunter engaging in his feast, out in the woods, buck naked.

Re-read

In any medium, when you analyze what goes behind a finished work, it changes the lens from which you see and create from. I wanted to paste the excerpt here at the end so you can read it again. In addition to feeling the story, you have a parallel sense of why you're feeling what your feeling.

“Breakfast is the only meal of the day that I tend to view with the same kind of traditionalized reverence that most people associate with Lunch and Dinner.

I like to eat breakfast alone, and almost never before noon; anybody with a terminally jangled lifestyle needs at least one psychic anchor every twenty-four hours, and mine is breakfast. In Hong Kong, Dallas or at home — and regardless of whether or not I have been to bed — breakfast is a personal ritual that can only be properly observed alone, and in a spirit of genuine excess.

The food factor should always be massive: four Bloody Marys, two grapefruits, a pot of coffee, Rangoon crepes, a half-pound of either sausage, bacon, or corned beef hash with diced chiles, a Spanish omelette or eggs Benedict, a quart of milk, a chopped lemon for random seasoning, and something like a slice of Key lime pie, two margaritas, and six lines of the best cocaine for dessert…

Right, and there should also be two or three newspapers, all mail and messages, a telephone, a notebook for planning the next twenty-four hours and at least one source of good music…

All of which should be dealt with outside, in the warmth of a hot sun, and preferably stone naked.”

- Hunter S. Thompson, 1979

Dean's List

Join to get new posts in your inbox.