🔦 Run-ons & Spotlights

Virginia Woolf knocked out sentences that could stand alone as their own atomic essays.

Upwards of 200 words, the sights, and sounds, and things she heard, they burst out from her mind, in between commas and semi-colons, giving you the chance to vacation in her daydreams.

Woolf would "sketch" scenes, but her British rambles had a method.

She was a master at building patterns and then breaking them, in a way that was unexpected.

This >

This >

Still this >

Most likely this >

Most definitely still this >

This >

This >

THAT! Jesus, that?

She was a comedian, but joked through beauty and horror. Her work is filled with dramatic run-ons, where all signs point in one direction, but then as soon as you feel oriented, she hits you with a curveball.

"Mrs. Dalloway" is recognized as the origin of stream-of-consciousness novels. Behind the rambles, she had an intuitive sense of how to throw in logic twists, which is where she often hid her most important ideas.

By analyzing a few of her sentences, we can learn how to use structure to shine spotlights on the ideas that matter.

Beauty & Terror

Example 1: Contradictory Emotions

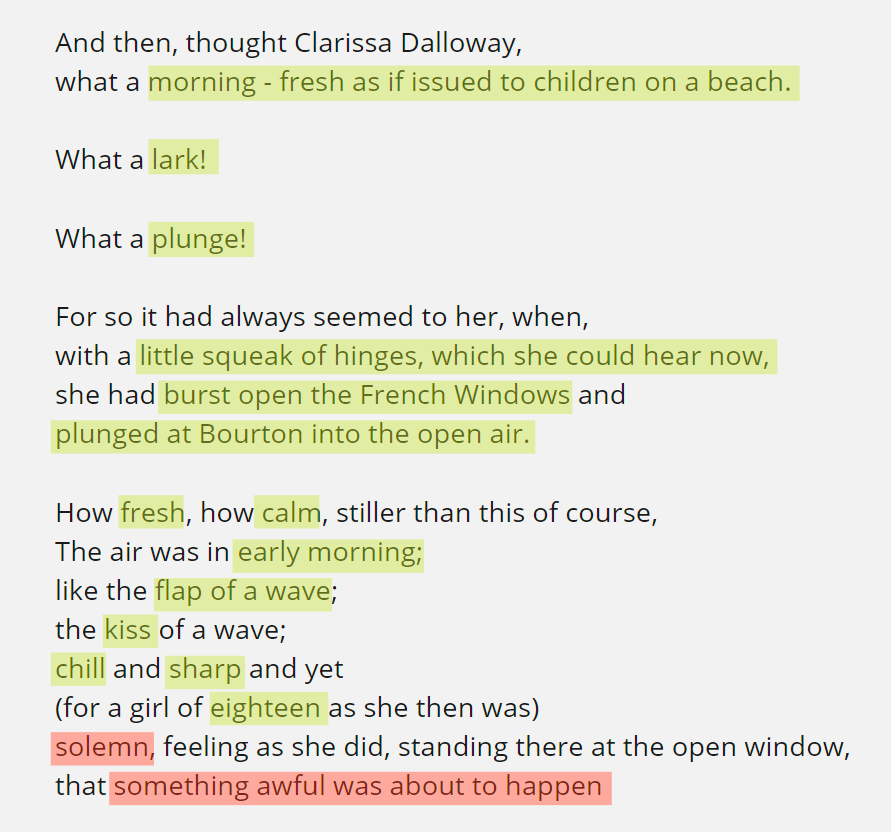

From the first sentence, we learn that Mrs. Dalloway is on her way to pick up flowers. After setting the scene with a few simple sentences, we get our first exposition.

She shows us the beauty of the day through a flashback to her past, and two metaphors that weave together.

- The image of innocent children on a calm and fresh beach, in the early morning, with chill and sharp waves.

- The feeling of opening a window and bursting through it like an energetic bird (a lark), into the city of London.

There are 14 symbols of serenity, all highlighted in green. But then, at the very end, she catches you off guard and lands on unexpected doom.

Coming from her lucid descriptions of birds and beaches, you wouldn't expect her to land on a world war.

On the next page flip, we learn that this book is really about the cultural shock that followed World War I (disguised as an adventure to pickup flowers for a party). Regardless of the beauty in her memories, there is a weird shell-shock that colored her flashback.

She built up a mood of innocent beauty, and then poked a hole in it, injecting you with paranoia.

The interruption of her train of logic creates a spotlight, and she chose to drop a cliffhanger there. Instead of telling us about the war, or showing us violence, we're left with a strange suspicion that beauty is an illusion not to be trusted, and we understand why two pages later.

Others vs. Me

Example 2: The range of society

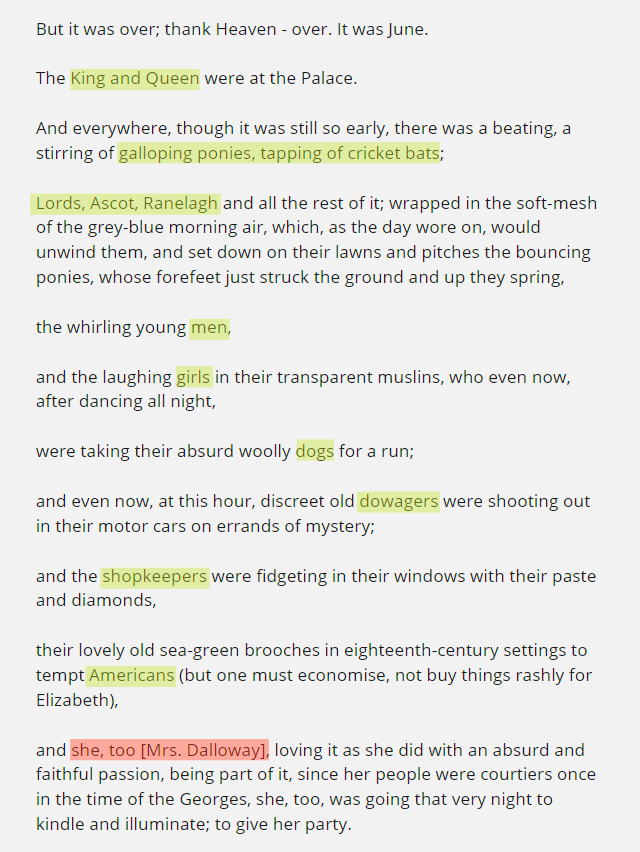

So in page 3, we learn the story is set in London, in 1925, where people are still shaken from the first World War. She quickly shows us two scenes of her friends mourning, but then gets into a massive run-on showing us what the return to normal is like.

She starts off with a simple "The King and Queen were at the Palace," before exploding into a 216 words sentence, where she paints a portrait of London:

- The cricket games are resuming

- London's cities are met with pleasant weather

- The men and girls are out dancing all night

- Woolly dogs are getting walked outside again

- Dowagers (widows) are running mysterious errands

- Storekeepers are trying to trick the returning American tourists

Woolf gives us a flash of society, before we get to see what Mrs. Dalloway's is up to.

Other > other > other > other > other > other > other > other > other > me! [9 others > me]

In that last segment of the sentence, we learn that her ancestors were advisors to King George, and that she's in the game of throwing upper-class parties for aristocrats.

In the first sentence of the novel, we learn she's picking up flowers, and now we understand why: the flowers are for her party.

These two ideas, paired with the shock from World War I, are basically the high concepts that anchors the book.

Given that this detail is at the end, and contrasts the rest of the lucid portrait she's painted, it etches itself into your memory. She can rave all she wants about life in London, but she places key details at very intentional spotlights in her structure.

Write it in Reverse

An attempt

One simple way to build out a spotlight like this is to:

- Figure out the thing you want to convey,

- Put it at the end, and then

- Front-load it with various images that contrast it.

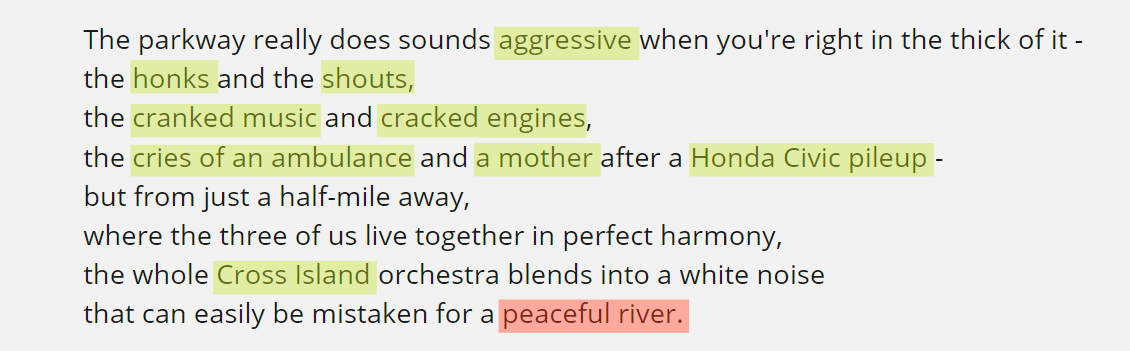

This paragraph I wrote is about how the Cross Island Parkway is chaotic when you're on it, but when you're far enough away, it sounds like a natural river.

Here's an attempt:

I knew "peaceful river" was the destination, so I wrote it first, went back to the front of the line, and then free-associated with loud, mechanical highway memories from my life, until I arrived at an opportunity to link it to the spotlight.

The takeaway here isn't that all of your sentences need to massive run-ons. We can't forget the little ones, but:

If you have an image you want to etch into someone's memory, you can build a contrasting scene in front of it to make it hit harder.

Dean's List

Join to get new posts in your inbox.